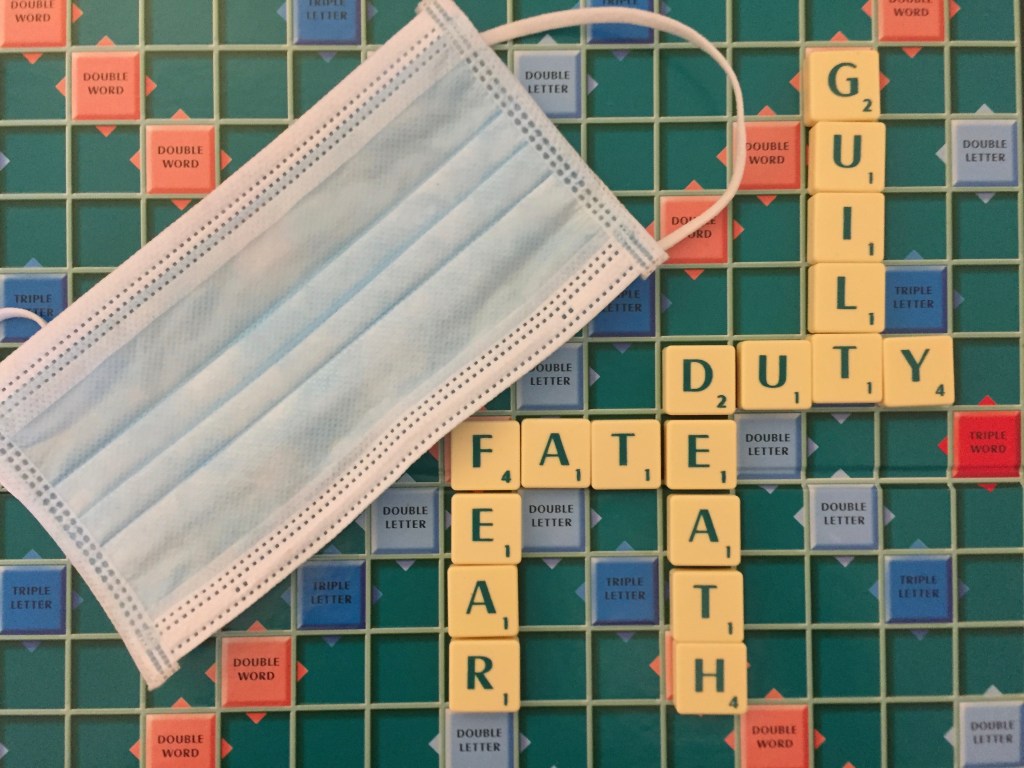

Reading a book about an epidemic in the midst of a supposed pandemic cannot but influence one’s take on the story. Nemesis recounts an (actually fictitious) outbreak of polio in Newark, New Jersey in the summer of 1944. At that time the virus that causes polio had been identified but the discovery of an effective vaccine was still more than a decade away. Polio epidemics were therefore greatly feared, the more-so because the disease saved its worst attacks for children and adolescents. Roth immerses us in the atmosphere of fear and anger wrought by this invisible assassin. Old prejudices are reinforced as anything and everything – Jews, Italians, hot-dog parlours or the mentally retarded are blamed for the epidemic. This visceral fear and suspicion feels a long way from Britain 2020 where fights over toilet rolls in supermarkets, or police arresting pensioners for protesting, contribute to the unreal atmosphere of a ‘pandemic’ where the average victim is over 80 years of age.

But if the polio epidemic provides the backdrop to this story, it gradually becomes clear that Roth’s real interest lies elsewhere. The ‘hero’ is a young sports instructor called Bucky Cantor. Bucky’s mother died in childbirth and his wastrel, thieving father took no role in his upbringing. Instead Bucky was raised by his grandparents, God-fearing, hard working Jews who raised Bucky to be a ‘real man’. In Bucky’s eyes that meant standing up, and if necessary fighting, for what was right.

When we first meet Bucky his self-esteem has already taken a battering because he flunked his army medical due to his chronic short-sightedness. So whilst his school buddies are now off fighting the Germans, Bucky is left in Newark teaching sports to the local kids during the summer holidays. He is idolised by the kids because of his athleticism and friendly nature. His reputation increases still further when he single-handedly faces down a group of Italian youths who come to his sports field to make trouble at the outset of the epidemic. But Bucky is not able to bask in hero-worship as an outbreak of polio soon begins to target his youngsters.

Within days of the outbreak one of his kids is dead and another is in critical condition. Bucky is badly shaken by these events and cannot comprehend how they can happen in a God-fearing world. Nevertheless he continues to do the right thing, visiting the relatives of the stricken children and continuing with his classes in the face of the polio threat. But his equanimity takes a further pounding when the mother of one of the stricken children shrieks at him that it is all his fault. Although understanding that this is just grief talking, this nevertheless causes the devil of guilt to start gnawing at Bucky’s conscience.

Whilst all this is happening, Bucky’s girlfriend Marcia is working at a summer camp in the Pennsylvanian hills – an idyllic spot far from the overheated cities where the epidemic is raging. She naturally wants Bucky to leave the city and come and join her at the camp, but Bucky feels it his duty to show solidarity with his kids by staying in New Jersey.

Anybody who has read Philip Roth’s earlier enfant-terrible stuff (e.g. Portnoy’s Complaint) will surely find this plot a bit staid. Both Bucky and Marcia are good, upstanding young people who embrace the values and standards of the society they were born into. Bucky is frankly a bit dull and his excessive sense of duty a touch exasperating. In fact one begins to feel that Roth has rather let down his characters in his eagerness to preach to us through them. The message, put into the mouth of Bucky’s prospective father-in-law, a folksy-wise doctor, seems to be that ‘a misplaced sense of responsibility cab be a debilitating thing’.

So it is eminently predictable that Bucky will abandon his responsibility to his city kids and run off to Marcia – and equally predictable that he will suffer for it (why else is the book called Nemesis). And so it comes to pass – after a mainly idyllic first week at the camp (dampened somewhat by episodic outpourings of guilt), polio arrives and the innocence of the summer camp is destroyed. Worse, Bucky is himself struck down with polio and comes to believe that it was he who brought it to the camp. He doesn’t quite say that it is pay-back for abandoning his kids but you get the picture.

The rest of the story is told in retrospect 27 years after the events. This again makes the story feel like a little morality tale where the key ‘take-aways’ are now highlighted for us. Bucky could not face being the vector of the polio outbreaks and so sentenced himself to life without happiness. He abandoned Marcia, despite her protestations, and spent the rest of his life alone enveloped in his guilt. It is true that Bucky suffered physical deformity from his bout of polio – the disease attacked both his left arm and his legs, as well as twisting his spine. But the real deformity was in his mind.

We find this all out during conversations with one of his former charges, Arnie Mesnikoff, who chances upon him in the street all those years later. Arnie too has been disfigured by polio but he has still managed to carve out a good life for himself, running a successful business, marrying and having children. But even he cannot convince Bucky that there is life after tragedy if only you will embrace it.

In this final retrospective section Roth’s writing is more literary and powerful than in the bulk of the book. Deliberate or not, this only emphasises how bland much of the writing is. Roth was in his late seventies when the book came out (2010) and it may be that he was just too distant from those young people to bring them to life. And what of all the nudges to the Greek classics – Nemesis, hubris, Odysseus, Hercules? I must say they didn’t really cast any particular light on the story for me. I get it that Bucky was brought down by a combination of misfortune and his ‘exacerbated sense of duty’. Bucky discovered that the world was chaotic, indifferent and beyond his control. That is something we all have to learn eventually – it’s called life. The real cause of Bucky’s demise was not fate. Rather like a Shakespearean hero he was destroyed by a fatal flaw – not greed, or ambition or suspiciousness but simple stubbornness. But if Shakespeare’s heroes are tragic Bucky is merely pathetic. And therein lies the real failure of this story.

Normally, I write my review and then read the other reviews – however, I read Joe’s comments on Nemesis and I am trying not to be influenced. I enjoyed the book – there were only a couple of pages where I got a bit impatient. I do think it was a good selection – topical, due to the dreaded COVID -19 and I think an anniversary of the vaccine. I did not realize that this was fictitious – after I finished the book I Googled and discovered Philip Roth grew up in this district of Newark. For me the book captures the hot and steamy NJ Summer very well – many of those kinds of neighborhoods still exist in NY and NJ. The cooler Poconos and the Summer Camp environment for the more privileged stands in stark contrast – except of course that polio like other childhood diseases is a great leveler. Anyway – I really like the way he captured the hot NJ nights and the daily concerns and idiosyncrasies of the the poor jewish community – we have also been watching Band of Brothers – so that part of the context clicked for me. A lot of suffering.

I thought I was very clever to pick up on the symbolism of the javelin – inoculating good and evil amongst the young charges Bucky was so protective of – the Italian crew was a red herring but reflected another dimension of prejudice – need to go for a swim and think about this some more…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that Roth’s descriptions of broiling summers in New Jersey and the summer camp are strongly evocative of a bygone age of American childhood. I was just a bit disappointed with where he took the story from there. The symbolism of the javelin is also interesting. This was Hercules’ weapon and the last few pages, the most lyrical in the book, take us back to the graceful athleticism of the young Bucky – a modern-day Hercules, brought low by fate, who destroyed his remains potential with self-loathing.

LikeLike

I was wondering if I am over-thinking this or the reverse? Is there another story being told about contamination or infection that is to do with race/ethnicity or social class – other wars…

LikeLike

I think Roth’s use of Greek analogs (as well as the Red Indian ‘theatre’ at the summer camp) was certainly a way to try to ‘universalise’ his message. Like many Greek heroes Bucky was dealt a bad blow by fate. Despite living in the 20th Century with all its scientific advantages over the ancient world, his destiny was shaped by his response to forces he did not understand and could not control.

n the end we are all slaves to our emotions…Roth also makes it pretty clear that (despite the epidemic at the camp) that middle class parents could send their kids away from the epicentre of the virus whilst the working classes were largely stuck in the cities. It was ever thus – whether in ancient Rome or plague infested London the rich and powerful always made a quick getaway whilst the poor remained to take their chances with fate.

LikeLiked by 1 person